Art Movements: The Italian Baroque

The Baroque was ostentatious and emphasized the presence of the viewer. The Italian Baroque destroyed the Renaissance conception of the ‘realistic window’ and moved toward depictions that were more akin to the staging of a play. Paintings make dramatic use of value, and figures in sculptures seemingly act as actors upon the stage. Baroque artists made seemingly stagnant art come alive like the characters in a performance. The goal of many Baroque works is to overwhelm and immerse the audience. Much of Baroque art was fueled by the Counter-reformation, the Catholic church’s response to the Protestant Reformation. During the Protestant Reformation was when the Catholic church started losing patronage to Protestant churches. Led by Martin Luther, citizens of Western Europe and beyond had trouble with the greed of the Catholic church - especially indulgences (slips of paper bought by church-goers that could get the person "out of hell"). New Protestants believed in being saved by faith alone.. The Council of Trent was a 16th century conference hosted by the Catholic church. The purpose was to slow the Protestant beliefs' growing popularity and dispel myths about the immorality of the Catholic church. The Council of Trent commissioned much of the Catholic art of the time.

The Italian Baroque took place in the 17th and 18th centuries primarily in central Italy. Works from the Baroque are theatrical, heavy, and dynamic. The Italian Baroque contrasted the precision of the Renaissance, but diverged from mannerism by involving the viewer to a much greater extent. During the Italian Baroque, prominent artists worked in many media including sculpture, painting, and architecture. The overwhelming and dramatic character of works during this time can be accredited to continuity between all media. For example, Gian Lorenzo Bernini was a well known sculptor and architect. Bernini was well known for his skilled work as a sculptor but applied lessons in spatial reasoning to the fields of architecture and planning.

He sculpted Ecstasy of Saint Teresa and designed the Forecourt of Saint Peter’s Basilica.

In dramatic fashion and rich materials, the sculpture depicts a cloistered nun’s encounter with an angel. In the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, Bernini frames the sculpture to draw the viewer into the work and to make the viewer part of the audience.

The Forecourt of Saint Peter's Basilica- Etching by Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Click here to take a look

Italian Baroque artists continue to astound audiences. Some of the most famous masters include Caravaggio, Artemisia Gentileschi, Borimini, and Bernini. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was born in northern Italy in 1571 and died in 1610. He was one of the most trailblazing artists of the Baroque movement known for his revolutionary use of light and tenebrism (click to learn more).

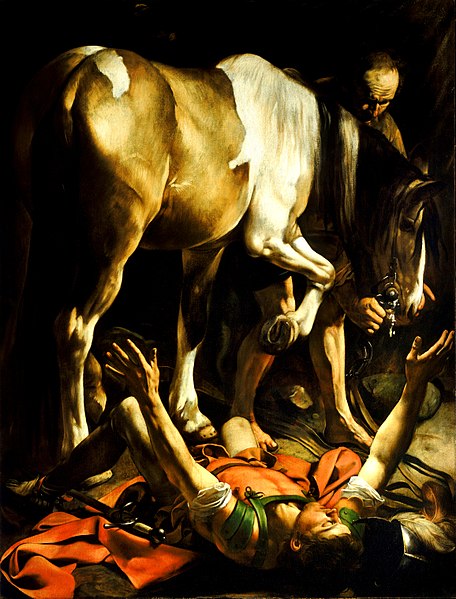

The Conversion of Saint Paul

In Caravaggio’s The Conversion of Saint Paul, he uses tenebrism to highlight certain figures and draw the audience’s eyes throughout the canvas. Caravaggio creates a composition inverse triangle with the horse, the head of the man on the right, and Paul’s head and arms. He uses the lighting in this painting to highlight these three points. The Conversion of Saint Paul is a prime example of Caravaggio’s work and the techniques that he consistently uses. Caravaggio as a person had a reputation for being violent and hot-tempered. Despite the fact that Caravaggio was not part of the elite, he was still a sought after artist. He changed painting impriablay by using non-traditional models. Caravaggio used the people in his paintings, because he wanted his paintings to appear realistic for the audience. His art drew much criticism from other contemporaries. One of them called Caravaggio “the antiChrist of painting”. During his life, he lived in Sicily, Rome, Naples, and Milan. Caravaggio inspired Baroque artists and had followers. One very significant follower of Caravaggio’s is Artemisia Gentileschi.

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in 1593. Her father, Orazio Gentileschi, was a baroque painter and a Caravaggio follower. “From her father, Artemisia learned the style of Caravaggio - intense reality, dramatic tension, theatrical effects of light and shadow - and another element that is rare among the Caravaggisti (click to learn more) , a use of beautiful luminous color,” editor of The Art Quarterly, E. P. Richardson said in his A Masterpiece of Baroque Drama. While Artemisia was a follower of Caravaggio, their artistic styles and depictions differ.

Judith and Her Maidservant-- Gentileschi

Judith Beheading Holofernes- Caravaggio

When comparing Caravaggio and Gentileschi’s depictions of Judith, the difference between them is obvious. Gentileschi’s Judith (left) is shown as a strong woman, while Caravaggio’s Judith looks fragile and pale. Artemisia Gentileschi studied under her father and one of his friends, Agostino Tassi. Artemisia was raped by Tassi. He promised to marry her, and when he did not, Artemisia and her father took Tassi to trial in 1612 for his crimes. It was a long and painful trial for Gentileschi. In 1616, she became the first woman to attend Florence's Academy of Design. Her trial and rape experience were trying experiences that fueled the emotion behind her art.

Late Baroque architect, Francesco Borromini, was born in 1599 and studied architecture in Milan. Borromini pushed the ideas of Italian baroque architecture. He was an advocate of the sculptural quality of architecture.

San Carlo alle Quattro - Exterior

Click here to take a closer look

The facades (click to learn more) of Borromini’s churches are not flat like most traditional ones, but they are curved. For example, one of Borromini’s most famous buildings, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, has late Italian Baroque techniques, including the audience. The facades ungulate, or curve, to pull the viewer into the church, much like Bernini’s work. Borromini distorts classical features such as the pediment to emphasize the middle doorway.

San Carlo alle Quattro- Interior Ceiling

He also changes the interior plan from traditional church plans. The walls have a different curvature than most churches. The ceiling is a softened, curved cross.

The Italian Baroque involved the audience, drew in the viewer, and was theatrical and heavy. Caravaggio, Artemisia Gentileschi, Borimini, and Bernini all pushed forward the Baroque style. They broke away from the precision of the Renaissance and involved the viewer, unlike the mannerists.

Vocabulary List:

Italian Baroque: the Baroque movement in the 17th and 18th centuries primarily in central Italy

Renaissance: the movement of art that was the transition between the middle ages and Modernity --started in approx. 1300

The Counter-reformation: the Catholic church’s response to the Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation: a time when the Catholic church was losing many followers to Protestant churches

The Council of Trent: an organization that commissioned Catholic art against Protestants and educated the public about Catholicism

Mannerism: AKA Late Renaissance; the art movement before Baroque: It’s art distorts the figures

Colonnades: a row of columns

Tenebrism: a technique of dramatic lighting

Caravaggisti: the followers of Caravaggio

Facades: the face of a building

Works Cited

"Artemisia Gentileschi." Britannica School, Encyclopædia Britannica, 3 Jun. 2008. school.eb.com/levels/high/article/Artemisia-Gentileschi/36435. Accessed 16 Jun. 2020.

Christiansen, Keith. "Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi) (1571–1610) and His Followers." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/crvg/hd_crvg.htm (October 2003)Further ReadingAdditional Essays by Keith Christiansen

"Episode #55: True Crime/Fine Art: Caravaggio the Murderer, and Murdered?" Jennifer Dassel. ArtCurious, created by Jennifer Dassel, season 6, episode 55, 14 Oct. 2019.

Gardner, Helen, and Fred S. Kleiner. Gardner's Art through the Ages: A Global History. Fifteenth edition, Student edition. ed., Boston [Massachusetts], Cengage Learning, 2016.

Liedtke, Walter. "Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669): Paintings." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rmbt/hd_rmbt.htm (October 2003)Further ReadingAdditional Essays by Walter Liedtke

NACE, NICHOLAS D. "Baroque in England." The Burlington Magazine, vol. 155, no. 1321, 2013, pp. 230–231. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23395423. Accessed 7 May 2020.

RICHARDSON, E. P. "A MASTERPIECE OF BAROQUE DRAMA." Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, vol. 32, no. 4, 1952, pp. 81–83. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41505132. Accessed 21 June 2020.

Rodriguez, Emily. "Baroque Art and Architecture." Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, 16 Dec. 2019, www.britannica.com/art/Baroque-art-and-architecture. Accessed 3 June 2020.

Sorabella, Jean. "Baroque Rome." Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Oct. 2003, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/baro/hd_baro.htm. Accessed 6 May 2020. Sorabella, Jean. "Baroque Rome." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/baro/hd_baro.htm (October 2003)

Sprinson de Jesús, Mary. "Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665)." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pous/hd_pous.htm (October 2003)Further Reading

White, Veronica. "Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680)." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bern/hd_bern.htm (October 2003)